When I was a teenager, I loved reading novels. I wanted to write my own, and eventually did, but more than that I wanted to be a published author. Getting published means going beyond the mere act of scratching words on a page. A traditional publishing house is like a seal of quality, guaranteeing that your work has exceeded a certain level. Anyone can write, but to be published makes you a professional writer.

I never got published. To tell the truth, I never wanted it bad enough. I submitted to many magazines, but I wasn't surprised when all I got for my troubles was a stack of rejection emails. It can take dozens or even hundreds of rejected submissions to make it to one acceptance. I didn't collect 100 rejections, so it's to be expected that I was never accepted.

I tell you this up front, so that if you want you can use it to completely write off what I'm about to say next as mere jealousy:

The traditional publishing industry is incredibly, stupidly broken, and deserves to go extinct.

But don't worry, there is still hope! I have a sure-fire plan to save the publishing industry, and deliver eternal glory to any of the Big 5 savvy enough to use my strategy... or even for an outside player to overturn the industry and supplant them all. What follows is an analysis of the problems facing publishing, and how anyone can solve them.

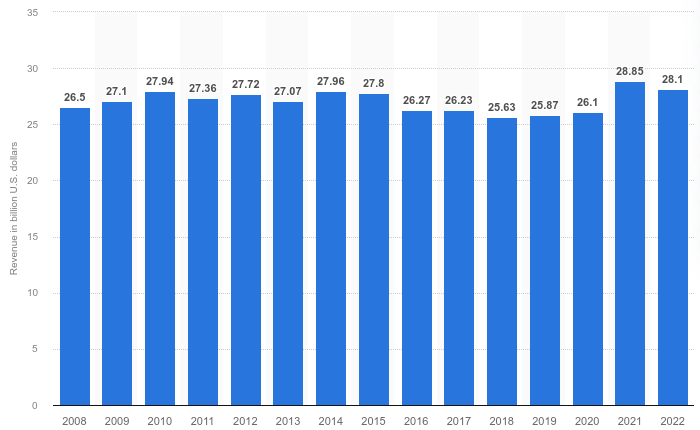

In order to convince you I have the solutions, I might have to convince you that publishing has problems, first. Let's start with total industry revenue, which has remained stagnant for years:

Amazon has a chokehold on the industry - somewhere between 50%-80% of publishers' revenue comes through the online retailer. As for Amazon itself, they don't really care about innovation in the publishing space anymore (unless you believe those rumors of a color e-ink Kindle for 2025). While book sales continue to make up a significant chunk of Amazon's retail businesss, they seem content with the current state of their monopoly. There is still plenty of room to outcompete the status quo, but Amazon themselves have no incentive to do so, because they have no real competitors, because books are kind of a creative dead end, as a product.

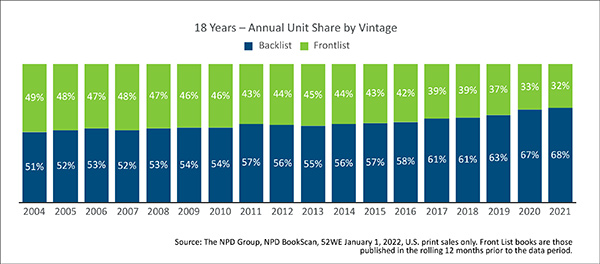

This lack of new development hurts new releases. Although revenue is stable, more and more of that revenue is coming from backlist titles:

This is because not only are publishers failing to launch new books into the market, they aren't even trying. The majority of books move very few units. Publishers themselves claim to have no idea how to sell books. The industry has given up. This abject acceptance of failure is the natural end result of an industry that refuses to think carefully and critically about its business as a business.

The broken state of traditional publishing right now can be represented as a chain of cascading errors:

Chances are, if you're disgruntled about the state of the industry, you can see your complaint somewhere in this list. All of these failures are downstream of ignorance — without understanding what makes a book successful, we can't appropriately deploy resources, and therefore can't support writers, and therefore can't break up the cliques. Our solution has to start with understanding.

That phrase usually implies hyper-specific content keyed in to certain consumer trends. Cookbooks targeted at fast-selling kitchen implements. Biographies about public figures dominating social media. Microgenres targeted at TikTok hashtags. All of these tactics can be successful up to a point, but they can never supplant the core business of publishing, nor can they sustain a frontlist of new and interesting books.

Instead of fixating on content trends, data driven publishing should pay attention to the context surrounding successful book releases, and modify that. After all, determining the content of a book is the writer's job. The publisher's job is to take the writer's work, and put it in a context where more readers will read it, whether that's the shelves of Barnes & Noble or an Instagram feed.

Look at Colleen Hoover. Look at this pull quote:

“She’s defying the laws of how the market works,” said the publishing industry analyst Peter Hildick-Smith. Most blockbuster authors break out because of a popular series, like “Twilight” or “Harry Potter,” or build a brand by writing in a recognizable genre. Hoover is eclectic. She’s written romances, a steamy psychological thriller, a ghost story, harrowing novels about domestic violence, drug abuse, homelessness and poverty. Though her books are hard to categorize, most of them have an addictive combination of sex, drama and outrageous plot twists.

Hoover's success as an author owes a lot to her talent in consistently creating content that millions of people want to read. But the context in which she became popular is something that publishers can learn lessons from. Every one of Hoover's books follows the exact same launch cycle: social media hype, ebook release (which Hoover typically keeps all profits from), backlist activity. Hoover attacked writing with a solid, replicable business plan, not as the first author to ever do it, only as the most successful. The content of her books is not what drives her sales.

Colleen Hoover is a case study in the pointlessness of content targeting. Her bestseller dominance is a result of extrinsic factors, things happening outside of the pages of her books. Traditional publishing should dominate in manipulating those external factors. Instead, Hoover had to build her brand alone, and traditional publishing only showed up after the hard contextualizing work was done.

The authors' guild claims hundreds of millions in losses due to piracy. (Incidentally, bullshit.) Publishers, while careful not to commit to such napkin math figures, do provide authors with anti-piracy forms that can be filled out for the publisher to submit a takedown request on your behalf.

When asked why they pirate books, the majority of people say convenience, not cost is the motivating factor. If publishers really want to assuage authors' fears about piracy, then publishers should create a context in which readers prefer to buy copies of books rather than pirate them.

Here are some ways to make a better experience than pirating:

Whoops, that's just a list of design principles behind Steam. Yeah, the guy who solved piracy as a service problem also has a de facto monopoly on digital storefronts in an industry twice as big as book publishing. Piracy will be solved as a natural consequence of creating a superior consumer experience.

One thing about highly invested book consumers is that they love fanfiction.

Wattpad has 80 million monthly active visitors, AO3 claims 7 million users, and other sites contain significant traffic as well. Too often, publishers adopt an antagonistic attitude towards fanfiction writers. Other industries would kill for this sort of user-generated content! If we're going to be offering Steam For Books, we might as well offer Steam's mod support as well.

Fanfiction should be encouraged. Fanfiction writers should have a space to host and share their work on the same distribution platform as the book it's based on. That book's dedicated forum should have space for discussion of fan works as well. Access to read and write fanfiction about a work should be largely unrestricted, with a single caveat: in order to read fanfiction about a work, you have to buy the book it's based on first. This turns demand for fanfiction into demand for the base book, and ties the community closer together rather than scattering them across multiple third party sites.

Community discussion should be encouraged in general. Amazon started to do this, with its acquisition of Goodreads, but Amazon's lack of focus on publishing caused them to miss the value of such a community. Discussion needs to be centered on the storefront, and in users' libraries — reading books we publish should be a communal affair.

Name recognition.

According to data from the recent DOJ-PRH lawsuit, there are three categories of books driving most of the revenue in the industry:

Or, to rephrase slightly, what sells books is:

Doesn't seem so inscrutable, after all. The value of name recognition will be the first pillar of our strategy to overturn publishing. When people recognize a name on the book, they buy the book. The name can be the author, or in the title, or the title itself. Simply buying the rights to a celebrity's name and having a ghostwriter pen their memoir will move copies. In order to create a context in which books sell, we have to build name recognition.

The way the movie industry builds name recognition is cross-pollenation. People liked Al Pacino, so they watched The Devil's Advocate and came out fans of Charlize Theron. This is easy with movies' giant production staffs, where a dozen names can all reasonably contend for space on a poster. Books can't reach that level of cross-pollenation, but they could stand to make an effort.

Publishers have unique relationships with lots of already successful names. IPs, authors, even imprints can be turned into recognizable brand names to move copies. Brandon Sanderson made his name completing The Wheel of Time; publishers should be nurturing hundreds of connections like that one. Group anthologies, collaborative series, periodical contributions — the literary world has tools available for cross-pollenation, if it would only leverage them. Publishers should drive that effort. They should connect collaborators, foster group work, aggressively promote collaborative works with name recognition. This happens to a degree already, but it ought to be the norm.

Corporate needs you to find the difference betwee-

The industry practice of cutting giant advance checks as the primary expenditure on a new book has got to stop. The cold truth of the matter is that publishers mathematically cannot offer competitive lump sums to authors in exchange for the amount of time spent on writing a book. The check will never be competitive compared to a day job.

Instead, publishers should focus on trying to get as many sales as possible for both their sake and the authors'. Authors Equity is an operation that gets this right. As they put it:

Our profit-share model rewards authors who want to bet on themselves. Profit participation is also an option for key members of the book team, so we’re in a position to win together.

Giving both parties stake in the success of the book encourages them to work together, rather than trying to mutually exploit. Publishers should take a proportion of the equity of a book commensurate with how much work they do. Once both author and publishing house are aligned on driving sales, that same metric can be used to evaluate editors as well. The more we understand the context that sells books, the more reasonable it is to expect that the people involved in producing the book create that context successfully, and wind up with sales to show for it.

Publishers should embrace self-pub as a viable business model that complements, rather than competes with, the more bespoke process of collaborating with an editorial team. However, publishers should also focus on developing the unique services that only they can offer: promotional circuits, production tools and processes, and of course distribution.

We have the building blocks for industry domination: an understanding of the fundamental problems, and solutions that speak to these problems in a way no one else currently does, backed up by proof of viability in other similar industries. However, to immanentize this revolution, we need a practical plan of attack. This plan will be different depending on the starting point we attack the industry from. Here's how this might work out for several viable approaches:

The natural choice of protagonist here is one of the Big 5 themselves. Any can work, although Penguin Random House might have an easier go of it than Macmillan. The advantages here are the deep backlist, financial stability, and industry connections.

A Big 5 strategy would be multi-pronged. On the technical side, aim to have a storefront+reader for ebooks with both web and mobile interfaces within 6 months. This is a community-building effort, not a profit-driven effort. Technical teams need to be talented and autonomous. This is not the place for cheap offshoring. Instead, save budget by aggressively pruning features that don't align with the mission.

On the operations side, a shift towards shared ownership with authors, and the production of collaborative works could start right away. Thematic collections based around a specific genre or subject matter can dip into the backlist and appropriate name recognition of past successful titles to encourage readership of new ones. Authors should be invited to take smaller advance checks in exchange for greater royalties, greater marketing support, and a higher likelihood of repeat publications. It shouldn't take more than 12 months for the first collaborative works and shared-equity titles to hit shelves.

The risks a Big 5 faces are mostly related to their established reputations. Such drastic shifts could spook authors, who are understandably protective of what they've managed to make under the status quo. There will likely be internal resistance as well, from editors who are used to having their way with content and leaving promotion to the authors. Even executive leadership could be a blocker, since the speed of development necessary to achieve success here seems antithetical to the Big 5's glacial pace of progress today.

Although all 5 mainstream publishers are financially stable, their pockets are not endless. The technical development here will be difficult to finance. A mediocre development team will absolutely kill the community engagement prospects of this plan.

Rather than holding out for a big dinosaur like Penguin to get up and evolve, a more realistic protagonist may be a small upstart publishing house. The advantage here is agility, and a lack of prior commitments binding them to old forms of business.

Starting with a clean slate, an independent press can take the time to define the author-publisher relationship correctly from the start. The press needs strong branding, a social media presence, and relationships with influencers, so as to be able to offer authors a competitive advantage over mainstream publishers. Marketing and design are important, but so is scouting talented writers to collaborate with.

Just like the mainstream publisher, our independent outlet should focus on collaborative works right away. Specialty imprint anthologies, collaborative serials, a monthly or quarterly magazine release, and guest features from creatives in other mediums will help establish value in the name of the press itself. That name brand recognition can be used in service of every writer who comes after, to increase sales.

Our independent press should probably hold off on digital storefront efforts until they're established as a brand worth listening to. When that does finally happen, chances are the brand reputation will attract developer talent with an interest and passion in the sort of aesthetics and experience we care about. Two years or so after launch is the time to start investigating this option.

The constraining factor for a small press like this will always be resources. Individual team members will be very important to the mission. The lack of a backlist will also frustrate efforts to rely on past successes to drive future sales, which is why building the brand rep is so critical.

My personal favorite, and by far the longest shot on this list, is to buy out Kindle (and maybe also Goodreads) from Amazon and spin it out into an independent company. While Amazon continues to make revenue on book sales, they devote tragically scarce developmental resources towards Kindle and the publishing space in general. Content to rest on their laurels, it's possible Amazon would allow Kindle some degree of autonomy in exchange for a shipping container of cash.

An independent Kindle should immediately focus on the digital storefront features. Kindle's design is outdated by a decade or more. Establish compatibility with more devices, integrate Goodreads directly into the store pages for books, and encourage forum participation. Build tools to empower authors to engage with their communities on and off the platform. Within the first year after development starts, the storefront should be redesigned and rebuilt. The Kindle firmware could use a round of refinement as well. Stop nickel-and-diming authors for impressions on their books; rely on recommendation algorithms to drive traffic, and advertise that the algorithm can no longer be bribed, so that people start trusting it more.

Amazon's physical printed books are impressively horrible — most consumers would be better served stapling together printer paper to get a physical edition of their digital titles. Acquire a small press with some actual experience producing books within 6 months, and run them like the independent press example above. Don't bother trying to materialize every self-published novella, instead build a trusted brand that people are excited to buy from regardless of content. For an example of tech bringing strong branding and curation to publishing, check out Stripe Press, the fintech giant's idea germinator.

The risk with Kindle is that old ideas about monetizing via ads are deleterious to the mission. Money should come from sales. Also, the relationship between career authors and Kindle is still tenuous. To supplant traditional publishers, we would need to demonstrate more trustworthiness than them. Being a tech company gives us a leg up on storefront and community platform building, but puts us on the back foot in terms of relationships. We can't develop solely for the smallest possible user.

Publishing is in a rut. If it were possible to reform it in a single blog post, it would have already happened by now. The good thing is that this is not an all-or-nothing plan: even achieving a single one of the solutions discussed here could be enough to run a stable business. Heck, simply making these problems more visible would be an achievement.

My ambition is to upend publishing. To do that, I believe we need at least this much radical change — ideally ten times more. Not just because the industry isn't as profitable as it could be. Not just because I hate Amazon. I hate the chain of cascading failure I described above. I am disappointed in the state of the industry. Partial success would be great, and as a reader I would love simply having a Goodreads replacement that isn't abandoned, or more bespoke imprints that aren't just celebrity vanity projects. But even more than that, I would love to change the entire dynamic around publishing, eradicate the toxic competition for editors' arbitrary favor, undo the severe austerity imposed by limited sales, and use the resources and capital of the industry to empower creatives to succeed or fail on their own terms, by giving them a consistent, predictable context to work in.

The more cynical among you might suspect I only want to build influence in the publishing industry in order to get my own work in print, and finally avenge my wounded ego that I mentioned at the beginning of this article. Don't worry, I promise to use a pseudonym for my fiction when I'm King of Books. With that settled, I trust that there are no further objections. If by some chance you do have questions or concerns about this strategy, feel free to let me know.

Thank you for reading.